U is for the Upanishads

My grandfather, nana Mahesh Chandra, who retired at age 60 and lived till 99, spent forty glorious years of his life just translating and annotating the Upanishads. Almost everything he had to say on the subject was echoed by the common man on the street. When I did ethnographic research in Banaras in the 80s, one of the many pleasant surprises about "everyday life in an Indian city" (my research topic) was that everyman was a philosopher. Thus this compendium of teachings that comprises the thousands of years old texts starting from pre-Buddhist times are ingrained in the common sense of people. The Upanishad is us.

Here I want to talk specifically about how this philosophical and pedagogical perspective may be made relevant to teaching, learning and children.

Teaching Indian philosophy is to teach philosophical concepts of course—but, more important, it is to teach in a certain way, and to teach how to learn, think and know in a certain way.

Can you tell us what these ways are? What techniques of knowledge and imparting and getting knowledge are peculiar to this Indian tradition?

That was a clue. The world calls the Upanishadic method "the Socratic method." According to it, you follow a method of asking questions and leading the student, through their answers, to uncover the chosen field of knowledge. You believe that knowledge can be acquired actively, not passively, by the learner. They will know and understand it better than if you had taught them in a top-down way with them as passive recipients of your knowledge.

In this set of literary-philosophical texts that succeed the Vedas, we learn that schools were home-based in ashrams or hermitages removed from settled areas. The teacher was the supreme authority and the culture of the school depended on his personality. Teachers were paid in service. Their students worked for them without negotiation. The teacher liked to keep his knowledge hidden or secret. One teacher assessed the quality of another by cross-questioning the student of the other. Each teacher, if a strong one, could have a separate school that revolved around him. Sometimes a student changed from one to the other voluntarily or through persuasion by the other teacher. Anyone could be the student, including a king or another teacher. Anyone could be the teacher, including a king or a woman or a young person who had been a student just recently.

The definition of "knowledge" was "the realization of truth." The highest truth related to immortality. The secret of immortality lay in awareness of the atman or metaphysical self, the perceiver who is not separate from the perceived. Knowledge was power. It consisted of knowing how to control the means to acquire land, gold, cattle, grain, household goods, friends, and so on, apart from knowing the self, and how to increase what is acquired. The teacher kept a score of the patronage and honors bestowed, and if slighted, demonstrated his power. The system continued to retain quality because of the competition between teachers for students, and for patronage.

In the Upanishads there are thousands of stories of students and teachers. Indeed a whole body of texts are called Aranyakas. They are set in forests where the teachers taught in hermitages and the students learnt through action and discussion. Unfortunately, when we want to present a picture of 'ancient India' today we show an emaciated man under a tree or a radiant yogi. Rather than that, we should drop our tired adult imagery and have more children use their imagination to create the images. We should focus instead on the precious method of the Upanishads.

Of the many famous stories from the Upanishads, two that are my favourite are those of Svetaketu and his father Uddalaka Aruni, and of the sage Durvasha. Because Svetaketu had become somewhat arrogant after his years of study, his father wished to balance that with a dose of humility. He asked him some key questions that the son could not answer but was honest enough to admit, "Teach me, father." Uddalaka was happy to do so and delivers some of the most popular messages of the Upanishads—all through interactive teaching.

As for Durvasha Muni, he is an exemplary model for those children who throw a tantrum at the smallest instance of a perceived slight. Durvasha Muni caste bitter curses to one and all, though, in all fairness, he often modified them when given explanations. It is valuable for children to feel that emotions, interactions, and behaviour are often continuous in the world of children and adults.

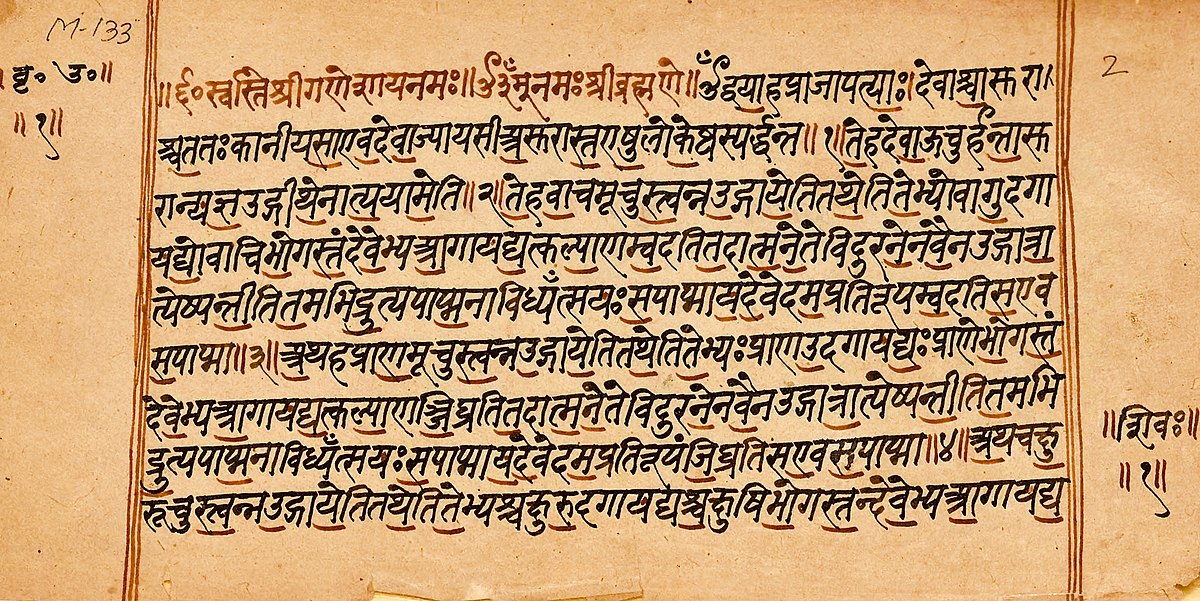

The other technique that has been used in India from time immemorial is that of memorisation. The Vedas were specifically learnt by rote, so much so that since they were originally only oral, not written, they were passed down generation after generation through centuries. What is very interesting is that the memorisation is not simply a rote one but one in which there are techniques to aid it, such as rhythm, melody, strategic repetition. Watch the recitation at 3.32.

The influence of Sanskrit education and its technique of rote memorisation was immense and is difficult to quantify. Rote learning served to give the student control over the dictionary of the language and the rules of grammar and literary analysis. It cultivated facility in pronunciation and respect for the structure of the language. By drilling in the discipline of the language, memorisation allowed, in the best of cases, the possibilities of the freedom to create that comes with perfect mastery of rules. Memorisation has received little respect in the present because it may easily be compared unfavourably to modern techniques of explanation and interpretation. However, it was an intellectually lucid approach to the aim of the system which was panditya or the total mastery over the grammatical and literary paradigms of a language that "legitimated" itself to become "a matter of dharma".

This memorisation came to be seen in colonial and modern times as responsible for the rote learning that characterised modern Indian education in general, and the learning of English in particular. Whether this is true or whether there were other more important reasons why modern education in India failed to live up to its ideal of liberal education, the meaning behind the pedagogic processes of Sanskrit education was certainly lost in modern times. We retained the shell of it in the rote-learning and not the holistic meaning of the technique.

A third technique is of storytelling and narrativization. It is still the way that villagers talk. If I ask Pandhari Yadav, what did Ram Khilavan tell you about the wheat? He will say, I went to his place on Friday. His son told me, chacha, he is not at home. I said, I will wait. I said to myself, if I have come all this way, what could be the harm of waiting half an hour? He came and said, chacha, have you been waiting long?........

Some of our storytelling is in songs and dances. Not only classical connoisseurs, but the whole world admires it. But we have forgotten in our modern teaching that anything may be taught as a story. Teachers, and parents, try these beginnings:

There was a time when….

A long time ago, there lived….

In a place called…. there was……

One day, when …. was sitting under a tree…..

You can start a Science topic by telling about the scientist. You can start a Maths topic by talking about the problem. You can start anything at all either with a real or a make-believe story, or simply a story about yourself or an imaginary person who finds out what you are going to teach.

Why did all this get lost and our schooling become so bland? Now, when we need ideas and inspiration, why do we always turn to the West? It's not our fault. In our own education, none of the Indian techniques were practiced. In our training as practitioners, they were not practiced, and the stranglehold of the West for two centuries was not broken either. So we have a scenario like this. The world is divided up into nation states. Each one is ethnocentric and considers itself the greatest and tries to promote its culture. There is one global culture in the world that we may call 'modern' culture. It is controlled by corporations that promote consumerism. So we have to plan what we need to do.

We need to have our children grown up as modern, global citizens and also as good Indian citizens in love with their country and its history, environment and culture. We have to make them so sharp that they can love their country while being critical of it, and appreciative of the rest of the world, but critical of it too.

Comments

Post a Comment